Variability and Consistency in Early Language Learning

The Wordbank Project

Preface

This website is the free online version of a book: Frank, M. C., Braginsky, M., Yurovsky, D., and Marchman, V. A. (2021). Variability and Consistency in Early Language Learning: The Wordbank Project. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Overview

The emergence of children’s early language is one of the most miraculous parts of human development. The ability to communicate using language arrives with incredible rapidity – most parents judge that their child is producing words with the intent to communicate before his or her first birthday (Schneider, Yurovsky, and Frank 2015) and the onset of comprehension is even earlier (e.g., Bergelson and Swingley 2012; Tincoff and Jusczyk 1999).

New words enter children’s expressive vocabularies slowly at first, but this process accelerates over the second year such that children reach an average of 300 words by 24 months and more than 60,000 by the time they graduate from high school (Fenson et al. 2007). At the same time, there are significant individual differences in the rate and timing of language acquisition. For example, although some 18-month-olds already produce 50–75 words, others produce no words at all, and will not do so until they are two years or older (e.g., Brown 1973; Bloom 2002; Clark 2016).

How do children learn their first language? To what extent do different children and children learning different languages follow the same path into language? Are these paths similar or idiosyncratic? These questions about the consistency and variability of early language lead directly into the central question of language acquisition: What are the mechanisms that lead to the emergence of human language?

Answering this question is complicated immensely by the fact that there is no one single event that constitutes language acquisition. Early language learning involves the accumulation of thousands of words, a host of grammatical rules and constructions, as well as the pragmatics of language use. This process takes place over the course of years of growth and millions of separate interactions. This problem of timescales makes measurement a tremendous challenge. In addition, during the period in which language emerges, language ability varies wildly from child to child and most children are at best reluctant experimental participants. Accurate measurement of language development across individuals is thus a major challenge.

Parent report is one powerful method for addressing these. The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI) is a simple survey instrument for measuring early language outcomes that was designed to address these issues.1 The CDI is a checklist for parents to fill out to report on their child’s progress in language. In different versions of the form, parents mark whether their child “says” or “understands and says” particular words out of a list of several hundred. Separate sections for gestures, word forms, and grammar are also present in some versions. Despite their simplicity, over the past 25 years of use, CDI forms have been shown to be reliable and valid measures of children’s early vocabulary size, as well as being a valuable tool for measuring other aspects of early language. In addition, CDI forms have been adapted to more than 100 different languages around the world. Research based on the CDI has contributed tremendously to our understanding of the growth of language in early childhood.

In this book, we examine the question of variability and consistency in early language through the lens of the CDI. Our book is an outgrowth of the Wordbank project (Frank et al. 2016), which has as its goal to archive CDI data in a structured format so that they can be explored and analyzed in the service of describing early language. The database currently contains data from more than 82055 CDI form administrations across 29 languages or dialects. Wordbank is also continuously growing as new researchers contribute data. We believe this database is the largest and most diverse set of data on early language acquisition currently in existence.

The first contribution of this work is unification. Over the course of our work with Wordbank, we have developed a consistent framework for representing and analyzing CDI data. This framework allows us to unify a variety of influential previous analyses of CDI data, from sex differences in learning to the relation between grammar and the lexicon and the representation of nouns in early vocabulary. Research in early language learning often is based on a fragmentary empirical picture, in which many important theoretical conclusions are based on analyses of transcripts from a small number of children, or analyses of experimental or parent-report data from English learners only. We hope that bringing together a large set of analyses of vocabulary data and implementing them consistently, openly, and reproducibly on the same dataset will help to create an empirical starting point for future work.

The second contribution of this work is generalization. By creating a systematic framework for evaluating prior analyses of CDI data, we are in a position to notice parallels between analyses, or paths left untaken by previous analysts. For example, after systematizing our treatment of noun biases in 11, we apply the same tools to analysis of semantic categories in Chapter 12.

The third contribution of this work is to develop theory treating the question of consistency and variability in early language. We introduce the notion of a continuum describing the relative consistency of phenomena across languages and cultures. At one end of this continuum are phenomena that exhibit substantial consistency and hence can provide clues to “process universals” – the aspects of the process of early language learning that may be shared across learners in very different circumstances. This notion contrasts with notions of “content” or “structural” universals in which specific principles regarding the structure of languages are innately given. The general idea of universals of process has a long history in the field (e.g., Bates, MacWhinney, and others 1989; Clark 1977), but the Wordbank project provides an opportunity to apply new empirical data and analytic power to these ideas.

This set of contributions reflects an important guiding principle of our work here. Studies which at first glance seem like “mere replication” – in which a particular analysis is replicated on a larger dataset – are in fact important opportunities for theoretical development. Replicating with a larger dataset typically leads to a more precise estimate of the phenomenon of interest, which can be used for confirmation, but also for quantitative comparisons and computational modeling. But this increased precision then allows for the examination of variability and consistency across meaningful units like children, words, instruments, or languages. Such estimates in turn are – as we argue throughout – relevant to foundational theoretical questions. Thus, there is never “mere” replication. More precise measurements sit hand and hand with better theory (Greenwald 2012).

Outline

The first chapters of this book provide an overview of the practical and theoretical issues that we cover. Chapter 1 gives a broad theoretical overview of our claims and sets up some of the empirical themes that we return to throughout, especially the notion of using the consistency and variability of phenomena to make generalizations about the process of acquisition. Chapter 2 then discusses the practicalities of the CDI and the Wordbank project. Chapter 3 gives a methodological and descriptive overview of the dataset we analyze throughout. And Chapter 4 discusses the psychometric properties of parent report data, addressing questions about the strengths and limitations of this method.

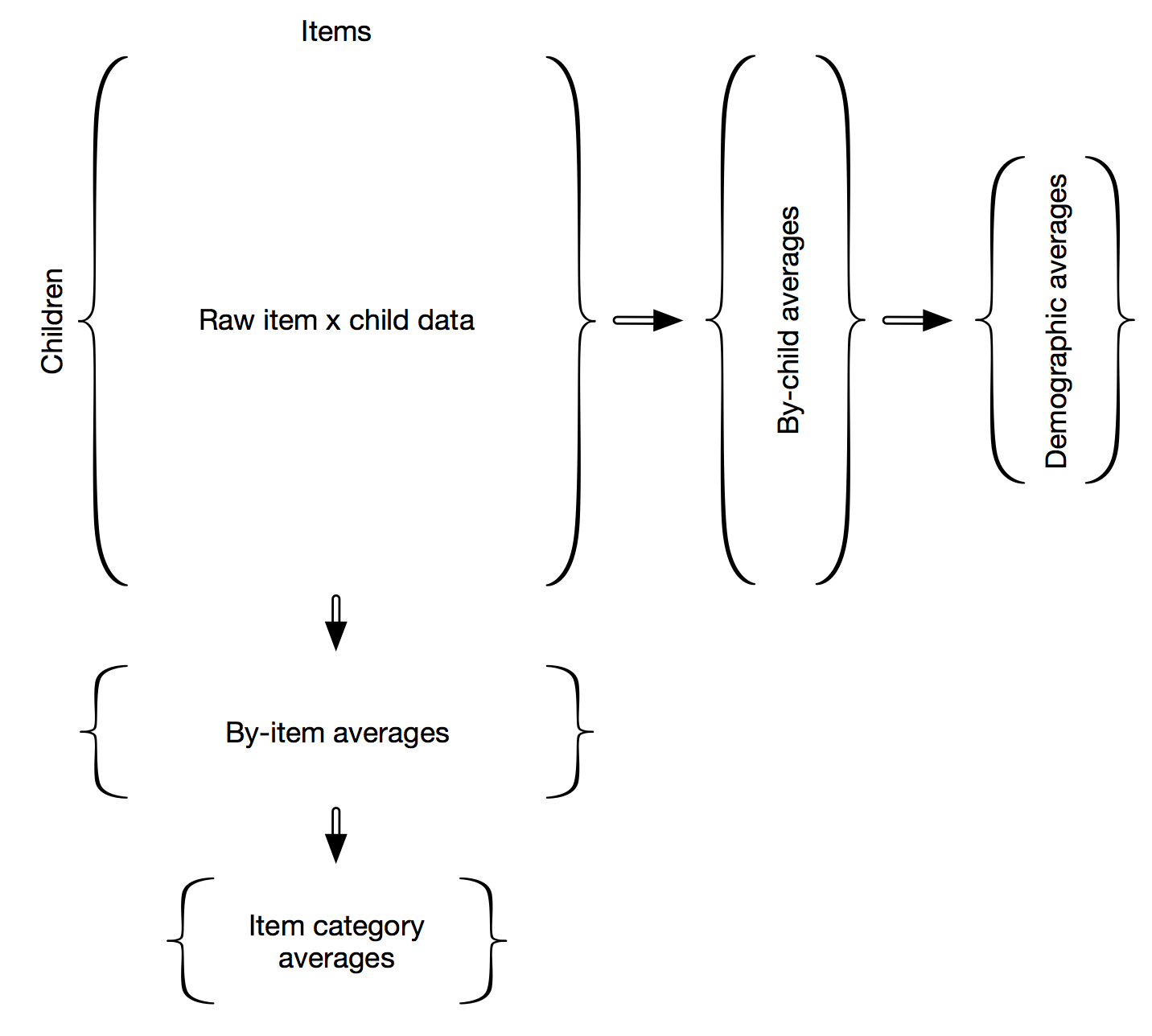

Chapters 5–15 then form the empirical heart of the book. Each applies a particular analysis of interest to our dataset. Although our goal is a full exploration of the phenomena of child language acquisition, the analyses we report are constrained by the structure of the data in Wordbank. At its heart, the individual instrument datasets stored in Wordbank are matrices of item by child data (see Figure 0.1).

Figure 0.1: A graphical outline of the book.

Considering the data in this way leads to a number of obvious data analytic strategies, many of which correspond directly to previous approaches to CDI data. For example, averaging across items leads to by-child averages, where each child receives a comprehension or production score. Chapter 5 considers this view of the data, examining developmental change and variability in such data. Then in Chapter 6, we report the ways that vocabulary growth varies across gender, birth order, and maternal education (a rough but cross-culturally valid proxy for socioeconomic status).

Averaging across the other margin of the data leads to by-item averages. These can be examined in a number of different ways. Gesture items and their growth trajectory – and relationship to overall vocabulary size – are examined in Chapter 7. Chapter 8 then considers the growth trajectories for individual words, focusing especially on early vocabulary. Chapters 9 and 10 follow this approach and attempts to predict the trajectories of individual words based on both environmental and conceptual features of these words. This last approach calls for the incorporation of other resources, and so we use a variety of English and cross-linguistic resources to supplement Wordbank data in this chapter.

Next, we investigate the grouping of items into categories (both syntactic and semantic). Chapter 11 considers the categorical composition of early vocabulary, giving special consideration to the “noun bias” that is found in many – but not all – of the languages in Wordbank. Chapter 12 adopts the same approach for semantic, rather than syntactic, categories. This approach leads us to consider other aspects of morphosyntax that are reflected in the CDI forms. Chapter 14 examines morphological generalization. Chapter 13 explores the relationship between vocabulary growth and the growth of grammar. Finally, Chapter 15 returns to the question of individual variation using tools built up in previous chapters to quantify differences in the style and trajectory of learning across children.

The book ends with three synthetic chapters. Chapter 16 synthesizes observations across languages for the preceding chapters to quantify variability and consistency directly across phenomena. Chapter 17 considers the question of what the process of language acquisition looks like from the birds-eye view afforded by our data. Finally, Chapter 18 considers methodological morals from our work here and the outlook on measuring children’s early language beyond the CDI.

Finally, the appendices describe and cite the individual datasets reported in Wordbank and provide supplemental analyses validating particular analytic practices that we adopt.

How to read this book

You can read this book as a narrative monograph. If you intend to do so, we recommend you read Chapters 1, 2, 3, and 4 before moving on to substantive chapters of interest.

You can also read this book as a reference. If you take this approach, just dive into any chapter that is of interest, knowing that you may need to use some of the terminology defined in Chapter 3 to interpret the constructs and analyses that are used. Further, you may have concerns about the reliability and validity of CDI-type instruments; these are addressed in Chapter 4.

A number of the analyses reported here were first described in earlier conference proceedings or publications (e.g., Frank et al. 2016; Braginsky et al. 2015, 2016, 2019). Rather than reprinting these verbatim, this manuscript updates them using the unified analytic approach and larger dataset described in Chapter 3. The version of these analyses represented in this manuscript should be considered more definitive than any previously published or presented version.

The dataset in Wordbank is constantly growing and changing as we add new features, new data, and new languages. In addition, as users of the data occasionally identify issues and errors, we make corrections to the database. In writing this manuscript, we have attempted to find a middle ground between a completely dynamic document that responds to any change in the database, on the one hand, and a traditional, static book, on the other. A static manuscript would be a shame given the potential for dynamic extension and updating with new data. On the other hand, if the data were completely dynamic, any claim we made in prose would risk being out of date almost as soon as we wrote it.

For this reason, we work using snapshots of the underlying database. Every so often, we will return to the manuscript and recompile the online edition, then check references to the data that might have changed. The current build of the book is from 2021-07-09 13:38:16.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks go to all of the generous researchers – too many to name here, but listed on the Wordbank contributors page and in Appendix A – who contributed their data to the database. Even during our time working on this project, norms of data sharing have shifted; some substantial portion of this shift is due to the generosity of those researchers who shared their data early on in the process. Thanks especially to Rune Nørdgard Jørgensen for sharing the full CLEX-CDI dataset (Jørgensen et al. 2010) and for his kind assistance in the transition from the CLEX-CDI website to the Wordbank website.

Major thanks are also due to the MacArthur-Bates CDI Advisory Board, especially Philip Dale and Larry Fenson, for their continued intellectual, financial, logistical, and personal support of the Wordbank project.

Thanks to Danielle Kellier for substantial work importing data and maintaining the Wordbank website, as well as updating the universal lemma mappings. Initial programming work was done by Ranjay Krishna, and some database imports were performed by Elise Sugarman.

Thanks to NSF Award #1528526, “Wordbank: An Open Repository for Developmental Vocabulary Data” for financial support of the Wordbank project as well as to the Stanford Psychology Department for a small seed funding award that supported the initial development of the site.

This book benefited from thoughtful comments by Philip Dale and Eve Clark, as well as comments on Chapter 11 by Dedre Gentner.

For purposes of clarity and ease throughout we refer to CDIs (the family of instruments) rather than the MB-CDI (the particular English forms). We will use this term throughout even though technically some of our data come from “checklists” containing only vocabulary items rather than true Communicative Development Inventory forms.↩︎