Chapter 7 Gesture and Communication

In addition to containing early words, CDI forms designed for infants (the “Words and Gestures” family) also contain a set of items designed to probe early gestural communication. This chapter explores these items. Our goals are to examine (1) the robustness of the measurement properties of these non-verbal parent-report measures, (2) the degree of cross-linguistic consistency and variability of reporting milestones like first pointing, as well as social routines like waving hi and playing peekaboo, and (3) the relationships between gestural development and linguistic development.

7.1 Introduction

Children’s most recognizable early linguistic accomplishments are surely their first words – a topic we turn to in the Chapter 8. However, even before infants approach this important milestone, they are already communicating through another modality: gesture. For example, a child who extends their hands and opens and closes their fist likely wants something to be given to them. A child who points to a bird up in a tree likely wants to get their caregiver’s attention so that they can share in the delight together. Children’s early vocalizations are also sometimes accompanied by gestures, for example, a child might raise both of their hands in the air and say “up!” The social and communicative routines that these gestures enable may themselves form part of the supportive context in which early language learning happens (Bruner 1985). In sum, gestures are an important aspect of children’s early communicative development.

Early gestures have long been thought to have a common mental status with later-developing linguistic accomplishments because both may reflect the child’s understanding of symbols, i.e., that a name or gesture can “stand in” for a thing in the world. The classic theories of Piaget (1962) and Werner and Kaplan (1963) proposed that all symbols have their origins in actions carried out on objects, and moreover, such symbols can be manifested in either the vocal or the gestural domain. These proposals suggest a common underlying mental function that is critical to the development of all symbolic skills, both language and in certain types of gestures.

While the strong representational claims in these theories may be too extreme by modern standards, they do correctly predict developmental continuity between early gesture use and children’s later lexical and syntactic development (e.g., Bates, Camaioni, and Volterra 1975; Thal and Bates 1988). For example, children’s ability to point to distant objects is linked to the onset of the production of first words (Fenson et al. 2007; Brooks and Meltzoff 2008), and children with delayed onset of pointing are likely to also be delayed in first word production (Clark 1977; Butterworth 2003). In addition, children’s early gesture use is correlated with their later comprehension abilities (Bates, Bretherton, and Snyder 1991), and children’s use of gestures in combinations with words is linked to the later production of multi-word combinations (e.g., Goldin-Meadow 1998; Iverson, Capirci, and Caselli 1994).

These early correlational findings could simply reflect a common cause: Children who use gestures might also be better at learning words. More recent studies have demonstrated more specific links between early gesture use and later lexical and syntactic development, however (e.g., Rowe and Goldin-Meadow 2009). For example, the particular lexical items that enter a child’s vocabulary are more likely to be names for those objects that are earlier labeled using gestures (Iverson and Goldin-Meadow 2005). Moreover, early gesture vocabulary is specifically linked to later word vocabulary, whereas early gesture plus word combinations are linked specifically to children’s later word combination skills (Rowe and Goldin-Meadow 2009). Taken together, the pattern of predictive correlations suggests that children’s early gestures provide an important social, communicative, and linguistic foundation for later language development.

Early gestures serve many different functions. Children typically first begin to use “deictic gestures,” for example, giving, pointing, and showing (e.g., Volterra and Caselli 1985). Such deictic gestures are clear precursors to important linguistic and communicative functions, including establishing reference and promoting shared attention (Carpenter et al. 1998). However, these deictic gestures do not necessarily have symbolic content per se (i.e., they do not stand for objects in the world, Bates et al. 1980). Early on, pointing gestures may serve a general imperative function, i.e. to request something from an adult. In contrast, later pointing is more likely to be referential, directing a caregiver’s attention to another object or person (Bates, Camaioni, and Volterra 1975; Masur 1990; Vygotsky 1980).

Children also use gestures as part of social activities, for example, waving “bye bye” or signaling “all done.” At first, social gestures might occur simply as imitations, but then later, children are able to produce these social gestures spontaneously in appropriate communicative contexts. Children’s social gestures also can reflect their ability to engage in activities during pretend play, e.g., talking on a pretend phone or pretending to stir a soup.

Finally, older children’s gestures also take on a “true” symbolic meaning, as a child might use a conventional gesture to recognize or classify objects as an instance of a category (e.g., pretend to drink from a cup or sniff a flower). Some theorists have hypothesized that children’s ability to use gestures in this symbolic way may reflect a common underlying “vocabulary” in both the verbal and gestural domain (e.g., Acredolo and Goodwyn 1985; Bates et al. 1980). These gestures may thus have a similar relationship to language as children’s pretend play (Bergen 2002; Smith and Jones 2011).

In sum, both early deictic gestures and later symbolic gestures have played an important role in shaping theories of communication and language learning. Thus, their cross-linguistic variability and their relationship to other aspects of language learning are important topics for investigation.

7.2 Measurement properties of CDI gestures

Following our work in Chapter 4, we begin by analyzing the degree of measurement signal in the gesture items. The available dataset is unfortunately significantly smaller than is available for vocabulary items – a number of users of the CDI forms did not measure (or at least did not provide us with data) on gesture items. Consequently, we focus first on the American English Words & Gestures form and use face validity as our primary criterion rather than a more sophisticated metric.

7.2.1 Measuring the development of gesture

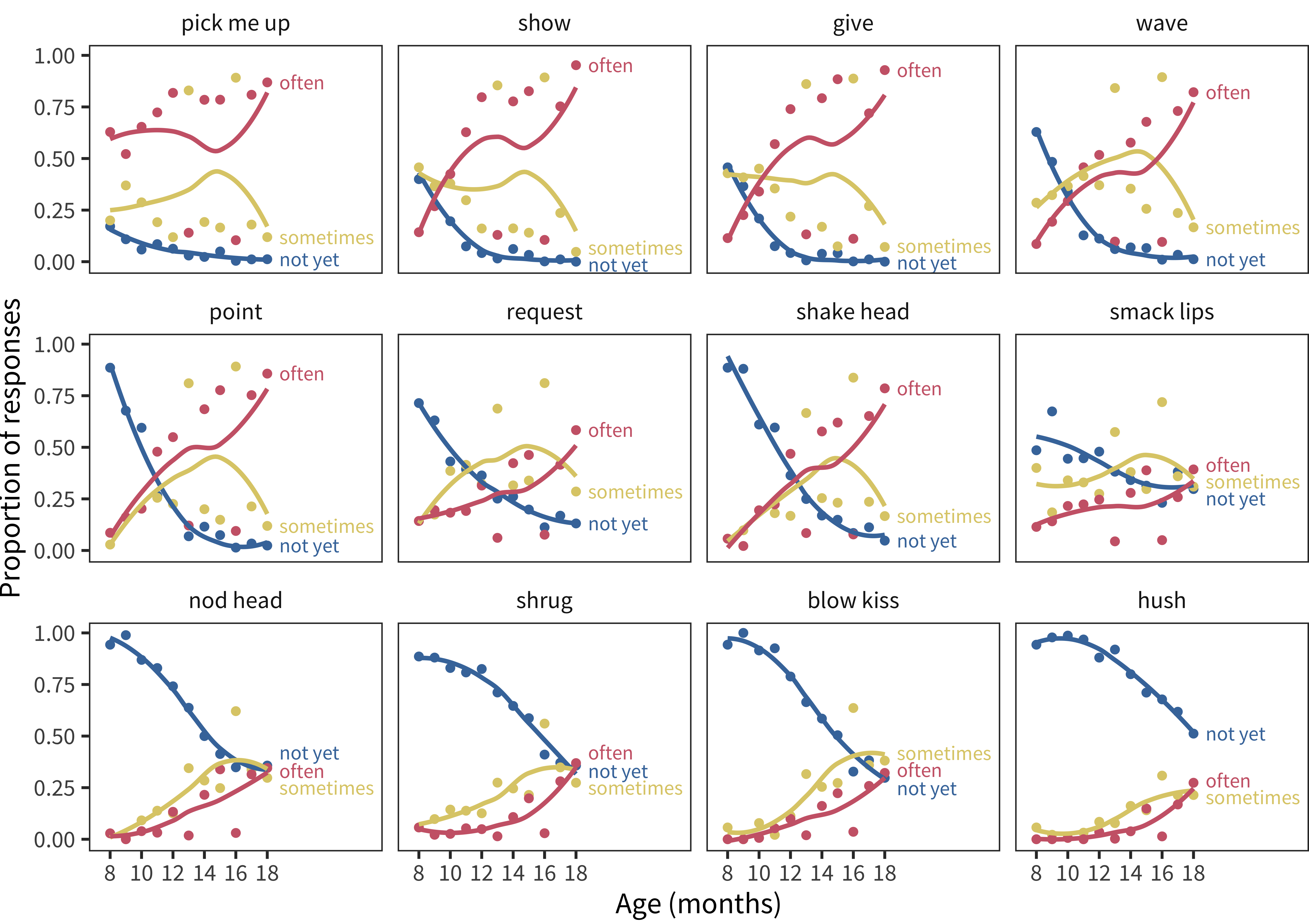

Unlike the word items on the CDI, which typically ask parents to make a binary decision about whether a word is in their child’s vocabulary (although comprehension and production are separate decisions), the First Gestures on CDI forms ask parents to make a 3-way decision, determining if their child produces a given gesture “often”, “sometimes”, or “not yet.” We begin by asking whether parents’ responses are sensitive to this distinction, as the choice of whether to treat all three levels as meaningful impacts downstream analytic decisions. We perform this sensitivity analysis on the American English CDI as it is the inventory for which we have the best a priori intuitions.

Figure 7.1 shows the proportion of American English learning children who give each of these responses. If each of the three responses is meaningfully different, the developmental trajectory of each should be distinct and predictable. The proportion of children whose parents indicate that they do “not yet” produce each gesture declines predictably over development. However, the other two responses – “sometimes” and “often” – do not appear to have reliably different trajectories. Perhaps they are used differently by different parents or in different samples.

Figure 7.1: Proportion of each response type over age on each First Gestures item for American English.

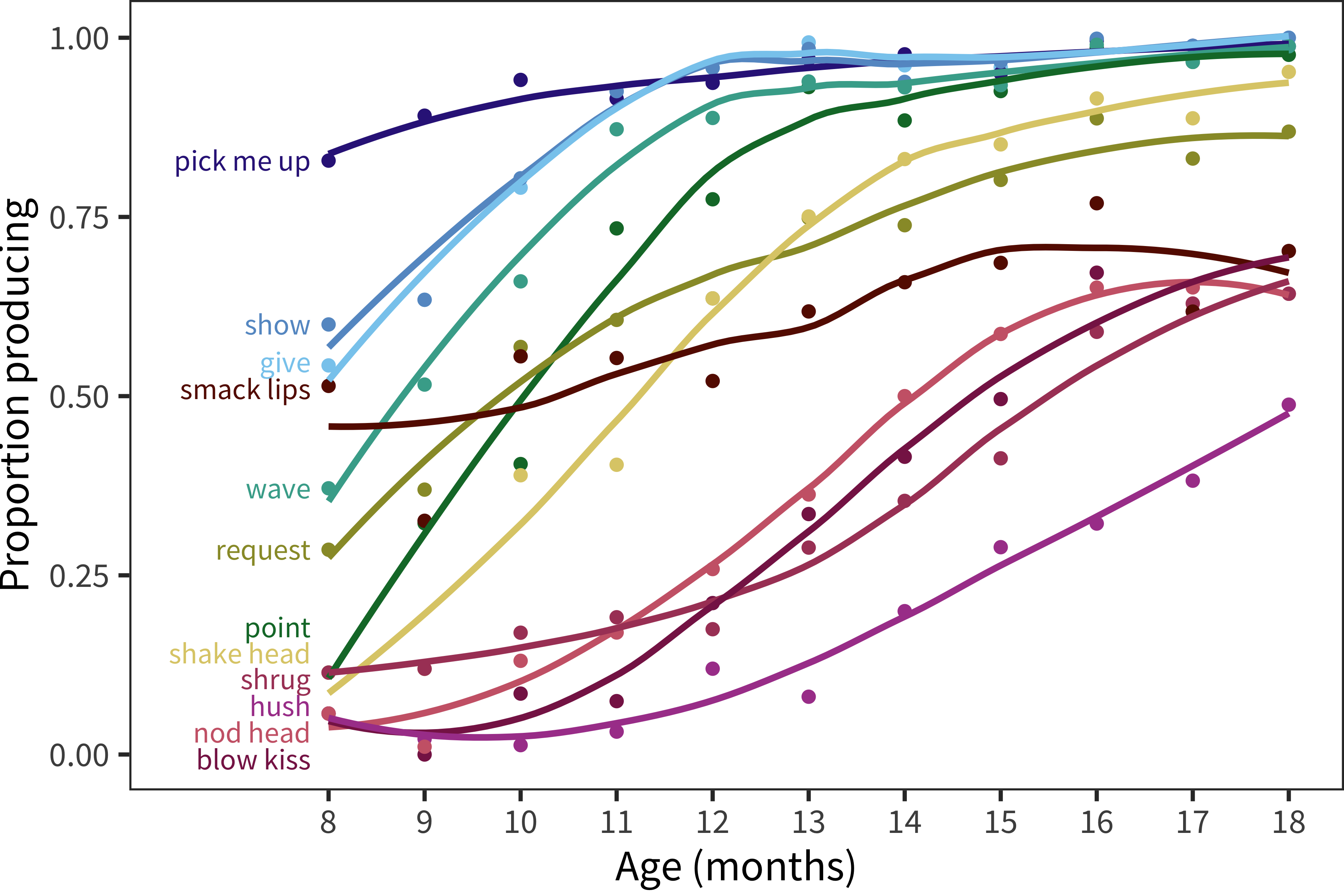

For comparison, we collapse the “sometimes” and “often” into a single value, and plot the proportion of children at each age whose parents report that they produce each gesture (Figure 7.2). The trajectories look generally smooth and prima facie reasonable, with the potential exception of the smack lips gesture for which there is very little developmental change (this gesture, which corresponds to the vocalization yum yum, may be unusual or less stereotyped).

Figure 7.2: Trajectory over age of each First Gestures item for American English.

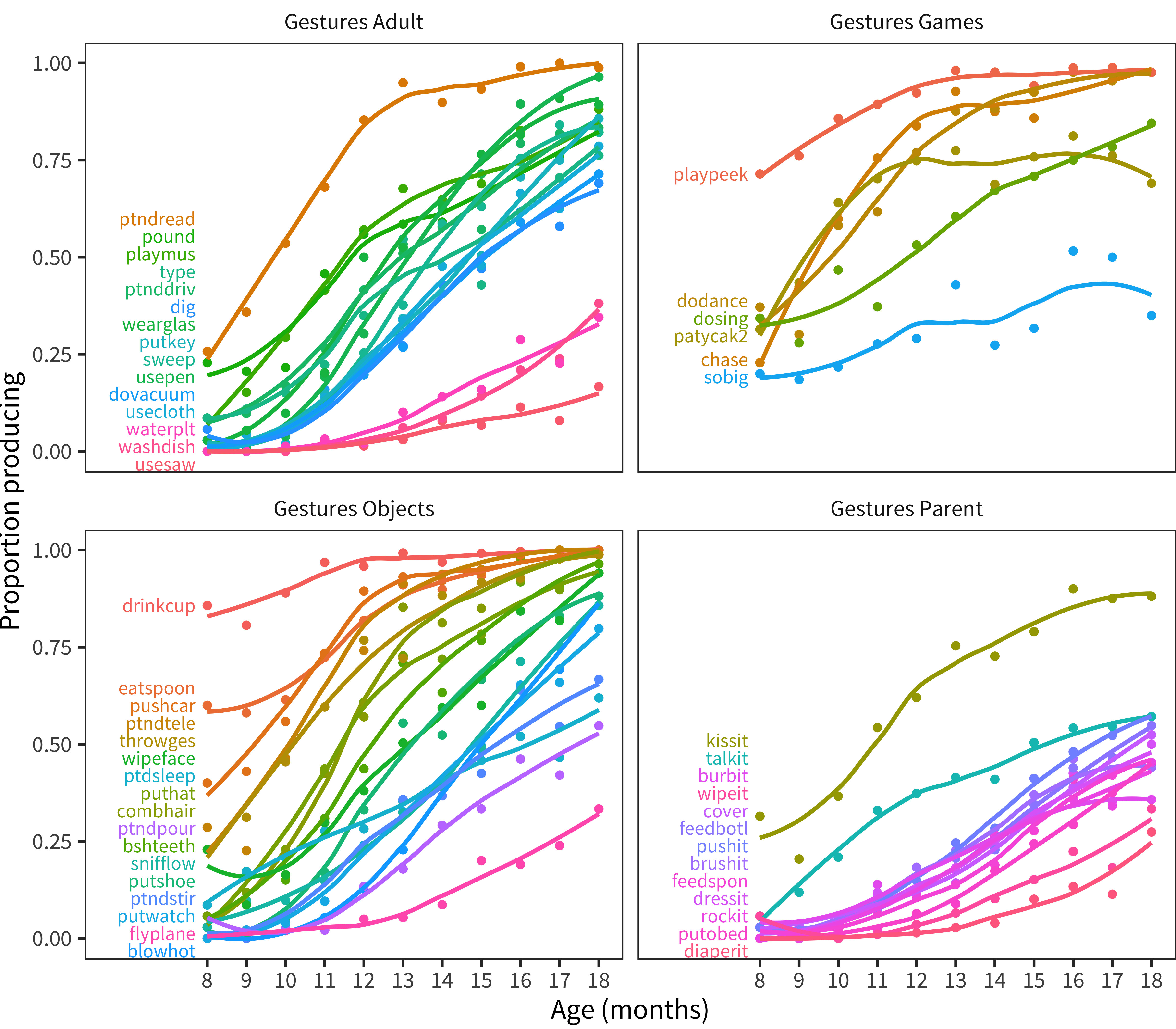

While these gestures are categorized on the CDI as “first gestures,” the form also asks parents about a variety of other kinds of gestures that children produce, including those involved in games and pretend play. Do these gestures have similar trajectories? Figure 7.3 plots developmental trajectories for these other categories of gesture.

While some are clearly learned later than the early gestures, a number of these appear to be learned quite early as well – for example, peekaboo and pretend play with cups and spoons. They all also appear to have generally smooth and increasing trajectories with the exception of so big (from Gestures Games) which, like smack lips from the First Gestures section appears to be either less stereotyped, more difficult to identify, or more variable across children.

Figure 7.3: Trajectory over age of each gestures item by type for American English.

Taken as a whole, it is clear that almost all of the gesture items have developmental trajectories not unlike word items, and that they thus have the potential for informative analyses. Further, trajectories look qualitatively similar across categories. Consequently, for general cross-linguistic analyses, we will consider all of the gestures together, and compress “often” and “sometimes” into a single affirmative choice.

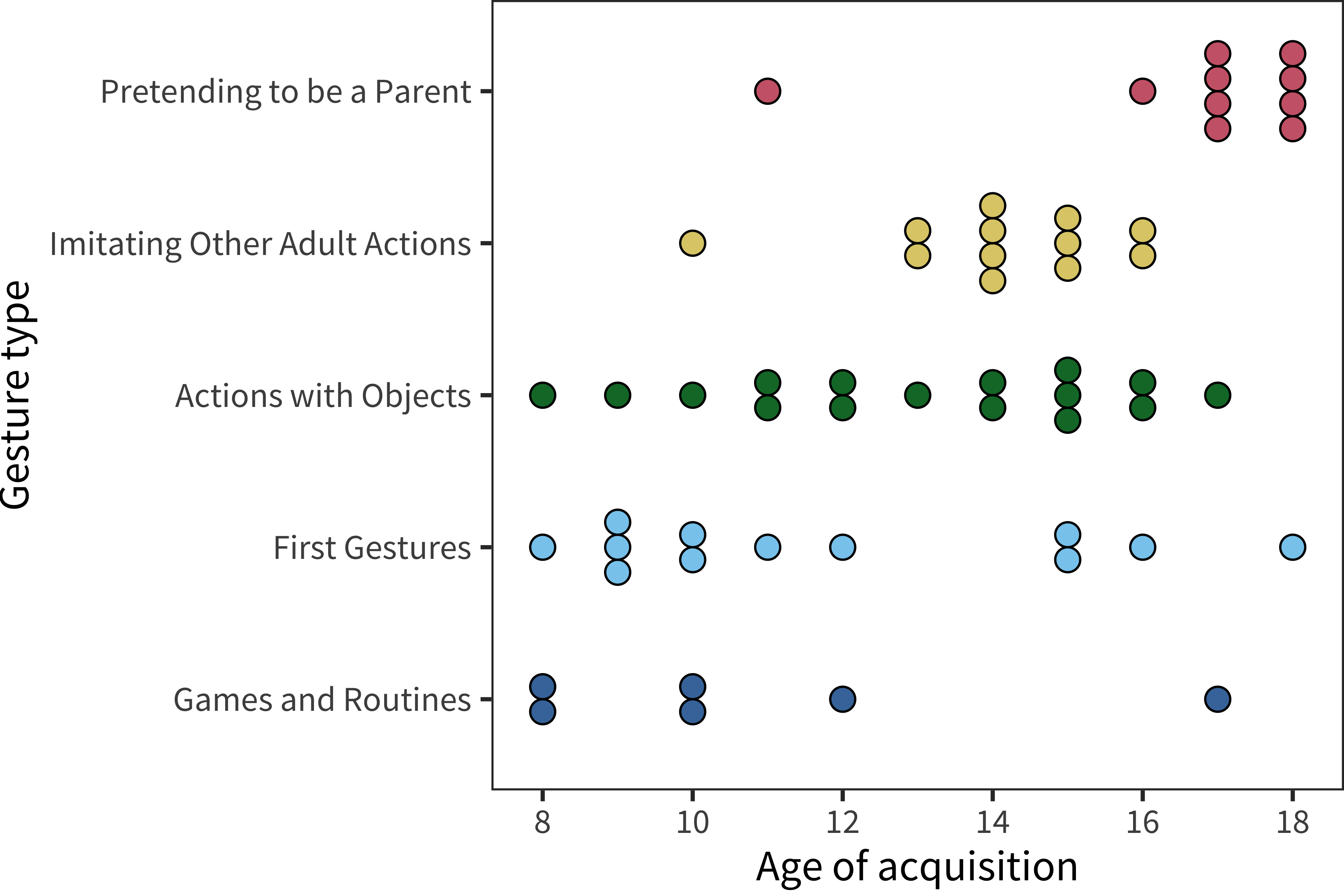

To estimate the coherence of these categories, we compute age of acquisition estimates for each of the American English gestures by gesture type: First Gestures (e.g. pick me up, point), Game Gestures (e.g. play peekaboo, chase), Object Gestures (e.g. brush teeth, push car), Adult gestures (e.g. type, use pen), and Parent Gestures (e.g. sweep, feed from a spoon). These estimates were produced by fitting a robust linear regression to the proportion of children who produce each gesture and estimating the age at which 50% of children produce the given gesture. The resulting ages of acquisition for each gesture type are shown in Figure 7.4. These categories vary in coherence, but overall First Gestures and Games tend to be produced early, and Adult and Parent gestures – more representative of pretend play – are produced relatively later (many not reaching 50% within the administration range of the form). The object gestures vary substantially in their ages of acquisition.

Figure 7.4: Age of acquisition for each gestures item by type for American English.

7.2.2 Consistency of the first gestures

While the First Gestures are not universally learned before the other gestures measured, they are among the earliest learned. Because of the particular theoretical importance of these early communicative gestures (e.g. deictics like pointing and showing, routines like pick me up), we analyze the cross-linguistic consistency of these at the item level.

| Item | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| show | 9.12 | 0.99 | 9 |

| give | 9.60 | 0.89 | 7 |

| shake head | 10.29 | 1.60 | 8 |

| wave | 10.29 | 1.60 | 8 |

| point | 10.40 | 1.67 | 8 |

| pick me up | 10.50 | 0.71 | 7 |

| smack lips | 13.75 | 2.06 | 7 |

| request | 14.33 | 3.21 | 8 |

| nod head | 14.50 | 3.78 | 8 |

| hush | 15.17 | 2.99 | 7 |

| shrug | 15.71 | 3.82 | 7 |

| blow kiss | 16.00 | 1.90 | 6 |

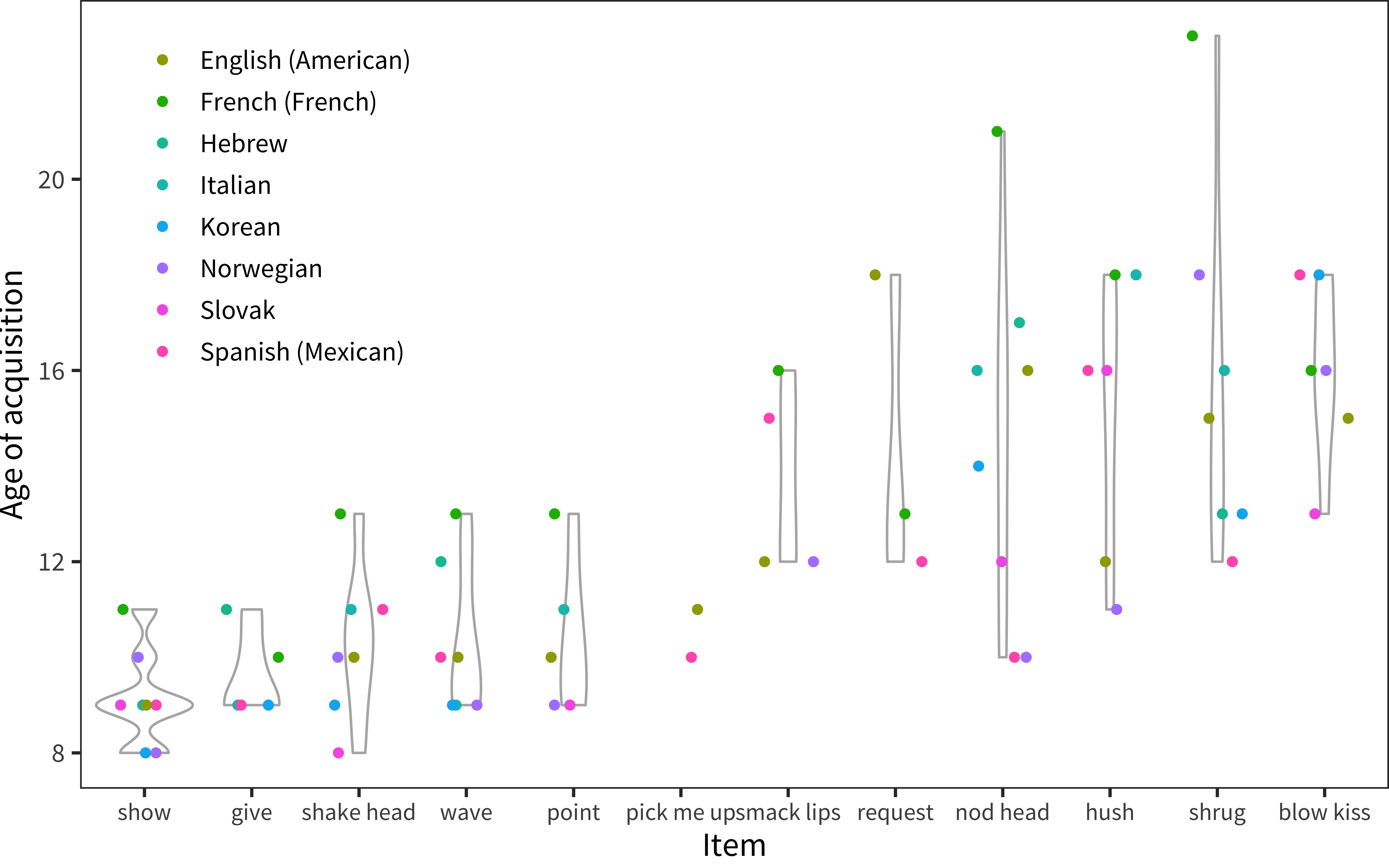

Table 7.1 and Figure 7.5 show both consistency and variability across items. As in the learning of words, the means and variances of these ages of acquisition were correlated (r = 0.81; Mollica and Piantadosi 2017). The primary outliers were request, which appears to be produced surprisingly late in American English, and shrug which was produced surprisingly late by French-learning infants. In general, however, most of the cross-linguistic differences appear to be consistent across the gestures (i.e. French-learning infants gestures later). It is difficult to tell from this small sample of mostly European languages whether these differences are driven by linguistic factors or rather by properties of our samples or variability in parents’ interpretation of the form. Nonetheless, they provide some evidence for consistency in the process of gestural development cross-linguistically. To get additional leverage on this process, we next consider the full set of gestures.

Figure 7.5: Distribution of ages of acquistion for each First Gestures item for each language.

7.2.3 Intercorrelation among gestures

Given both the similarity and the variability in the developmental trajectories of different gestures, as well as the cross-linguistic variability in first gestures, a natural next step is to quantify the relationship of gestures to each-other. We begin by computing the average intercorrelation between each of these gesture categories. In this analysis, we take gesture categories in pairs (e.g., Adult Gestures and First Gestures) and ask how the proportion of items that children know in one predict the proportion of items they know in the other. For American English learning children, the proportion of gestures they know across categories is correlated at r = 0.60 – nearly identical to the value of ~0.6 reported by Fenson et al. (1994). For comparison, the same intercorrelation computed across categories of words (e.g. “animals” and “places”) yield 0.64 for production and 0.57 for comprehension.

This cross-category intercorrelation is quite similar cross-linguistically, ranging from 0.56 in French (French) to 0.84 in Korean. The full set of intercorrelations is shown in Table 7.2.

| Language | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| English (American) | 0.600 | 0.113 |

| French (French) | 0.560 | 0.178 |

| Hebrew | 0.605 | 0.141 |

| Italian | 0.682 | 0.104 |

| Korean | 0.839 | 0.129 |

| Norwegian | 0.572 | 0.110 |

| Slovak | 0.687 | 0.080 |

| Spanish (Mexican) | 0.668 | 0.087 |

7.3 The relationship between language and gesture

A critical theoretical question in early communicative development concerns the relationship between language and gesture. As alluded to above, a number of early influential theories (e.g., Piaget 1962; Werner and Kaplan 1963) held that gesture and language should be intimately related because of their reliance on a shared system of symbolic reasoning. To the extent that they are underpinned by the same system, words and gestures should have related developmental trajectories – children who gesture early should also speak early and vice versa (Bates, Bretherton, and Snyder 1991). Following in the footsteps of Fenson et al. (2007), we ask this question at larger scale, and cross-linguistically. To assess this relationship, we will look at the correlations between children’s gestural and linguistic vocabularies.

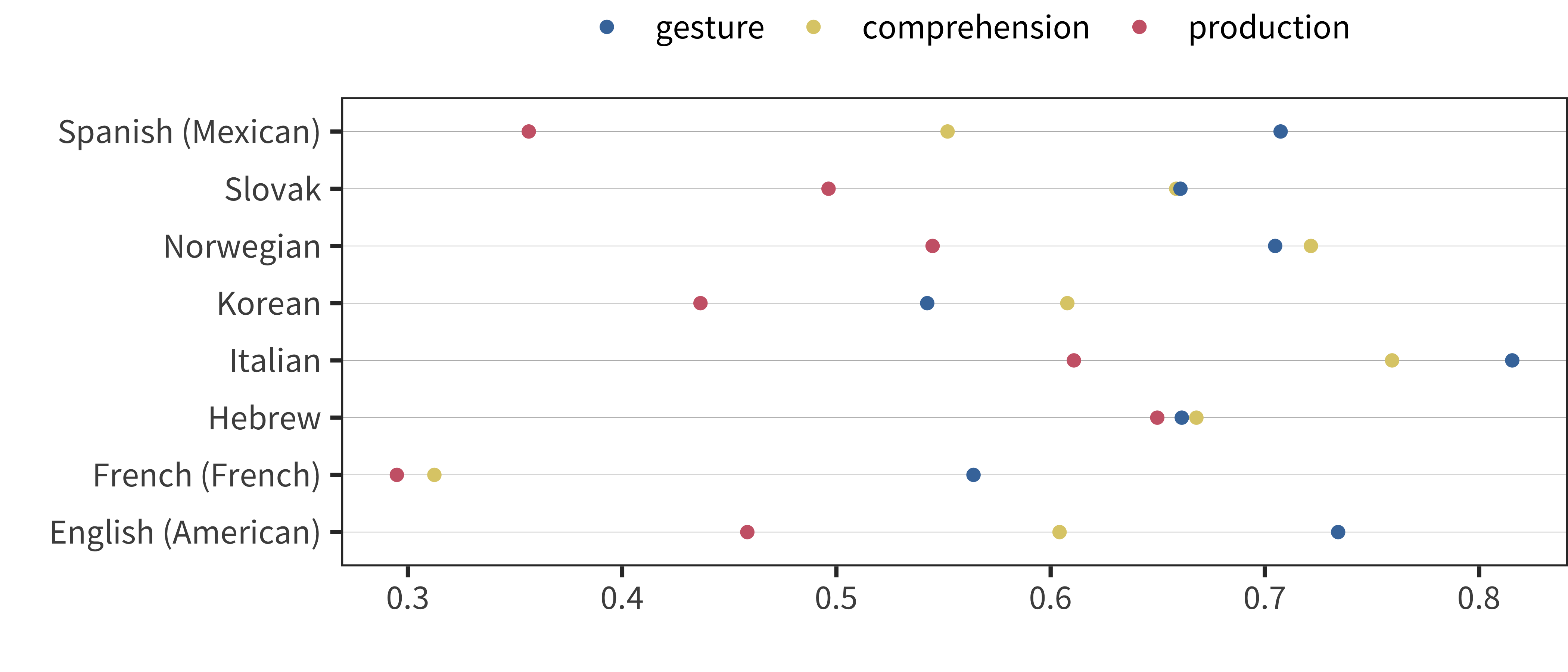

To first provide a baseline, however, we compute the correlation between children’s language and gesture development and their age. As Figure 7.6 below shows, gesture shows as much or more developmental change than comprehension and production – at least over the age range measured by the CDI Words & Gestures forms. The variability in the correlation with age in all three measures hangs together within languages: Languages where there is more developmental change in linguistic development also tend to have more gestural development. Production typically shows the lowest correlation, presumably because many childre are still at floor on this measure for most of the age range being measured.

Figure 7.6: Correlations between age and subscales (gesture, comprehension, production) across languages.

But what is the relationship between language and gesture? As both children’s lingusitic and gestural vocabularies increase over development, we should expect to see a positive correlation between language and gesture regardless of any interesting assocations between them. One way of getting leverage on their relationship is to exploit the difference between comprehension and production. As noted previously, comprehension and production do not proceed in lock-step and comprehension generally outpaces production. This is, in part, because production requires additional control over the developing motor systems necessary for speech. But it may also be driven by individual differences in children’s personalities or communicative goals: Some children may want to talk more than others (see Chapter 15).

To the extent that gesture and language are related by their shared reliance on symbolic understanding, their correlation should be highest when only this shared system is tapped. In this case, we should predict that gesture production and language comprehension are more tightly correlated than gesture production and language production. In contrast, if the correlation is due primarily to a shared desire to communicate and engage socially with caregivers, we should predict a stronger correlation between gesture production and language production. Across these 8 languages, children’s production of gestures is consistently more highly correlated with their comprehension of language than their production of language (Table 7.3). This analysis provides at least some initial evidence for the role of symbolic understanding in driving the correlation between language and gesture. An alternative explanation is also plausible, however – comprehension may simply show more variability than production in this age range, allowing for a higher level of correlation.

| Language | Comprehension | Production |

|---|---|---|

| English (American) | 0.75 | 0.53 |

| French (French) | 0.67 | 0.37 |

| Hebrew | 0.78 | 0.65 |

| Italian | 0.81 | 0.50 |

| Korean | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| Norwegian | 0.69 | 0.50 |

| Slovak | 0.63 | 0.54 |

| Spanish (Mexican) | 0.76 | 0.55 |

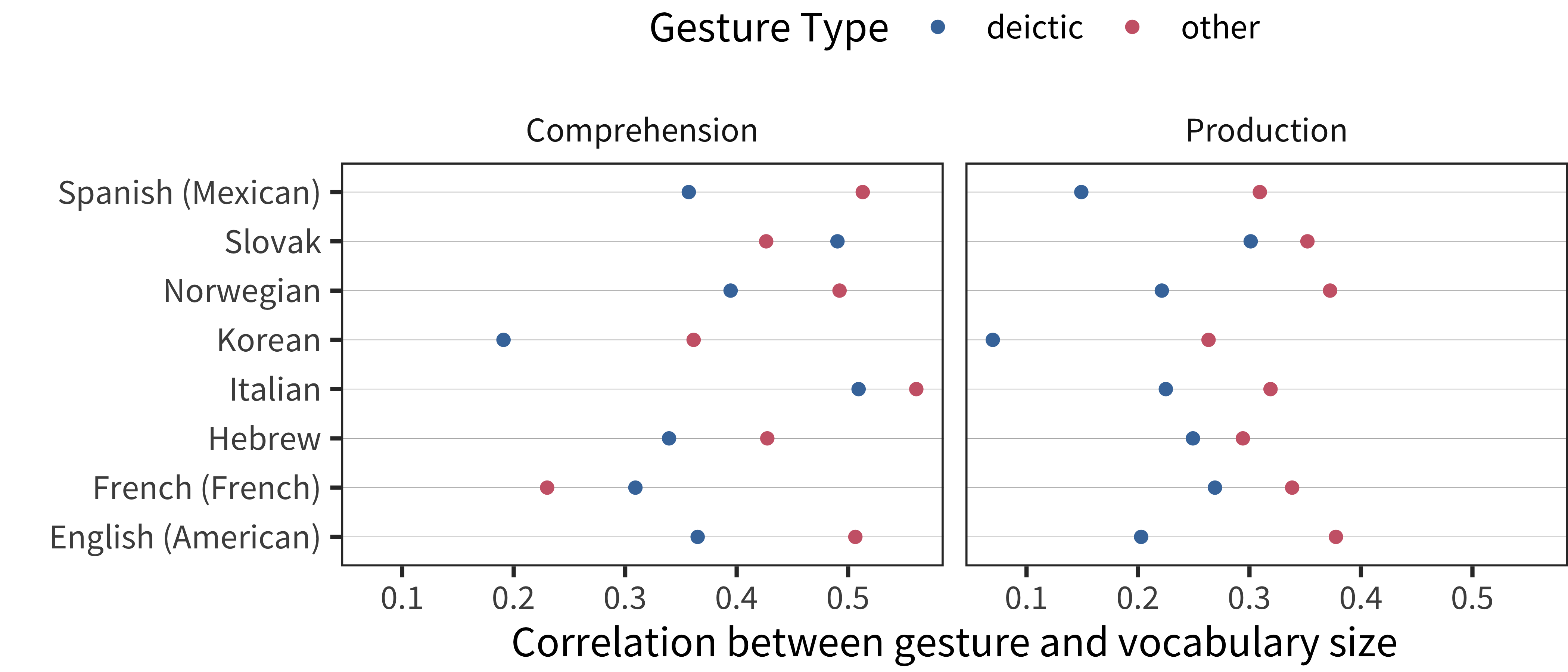

As a second, more specific test of this hypothesized relationship, we consider explicitly the deictic gestures. Deictic gestures are most closely associated directly with communicative goals rather than symbolic content: pointing, showing, and giving (Bates, Bretherton, and Snyder 1991). Because all of these gestures are produced by children relatively early, and thus contain less signal for older children, we compare these to the remaining Early Gestures that appear in at least 6 languages: wave, pick me up, shake head, nod head, hush, request, blow kiss, shrug. We excluded “smack lips” because of its lack of developmental change (see above). We then applied the same analytic method as above – computing the correlation between children’s gestureal and language development – seperately for these deictic and non-deictic early gestures. Because there are many more non-deictics, we take all 56 possible combinations of 3 of these gestures at a time.

Figure 7.7 shows deictic gesture-vocabulary correlations. As before, correlations between gesture and comprehension are higher than gesture and production, but in all cases language is more correlated with the children’s non-deictic gestural development rather than their deictic gestural development. This finding provides a second piece of evidence that the relationship between linguistic and gestural develompent is driven more strongly by reliance on a shared symbolic format rather than reliance on individual children’s motoric develompent or desire to communicate. Although this finding adds additional specificity to our analysis, we still mark this conclusion as tentative due to possible confounding with measurement issues.

Figure 7.7: Correlations between gesture and vocabulary size, for both deictic and non-deictic gestures, split by production and comprehension vocabulary.

7.4 Conclusions

Gestures appear early in young children’s communicative repertoires, with an understanding of the deictic purpose of pointing being found as early as 12 months of age (Liszkowski, Carpenter, and Tomasello 2007). The frequency of gestures in children’s input – as well as the precociousness of their own gesture productions – are also reliably correlated with their linguistic development (Rowe and Goldin-Meadow 2009; Brooks and Meltzoff 2008). In this chapter, we extended the analyses developed in Fenson et al. (2007) to look at these relationships cross-linguistically using large-scale CDI data.

In the first part of the chapter, we evaluated the measurement properties of the gesture items, as well as the coherence of the groupings of items on the CDI forms. Our analyses confirm that parents are likely able to report reliably on their children’s gesture development. We found a high degree of consistency in development of different gestures within child – children who learn some gestures early are also likely to learn other gestures early. Further, we observed a high degree of cross-linguistic consistency in the age of acquisition of different gestures.

Finally, we examine the relationship between gesture and language directly. We found that individual differences in gesture development were highly correlated with language development, and that gesture was more related to comprehension than production. Further, development of deictic gestures is less predictive of language development than development of non-deictic gestures. One speculative conclusion from these analyses is that precociousness in the gestural domain may be related to children’s developing understanding of symbolic communication systems, rather than shared motoric development or a strong desire to communicate with their caregivers.